Parler

Parler Gab

Gab

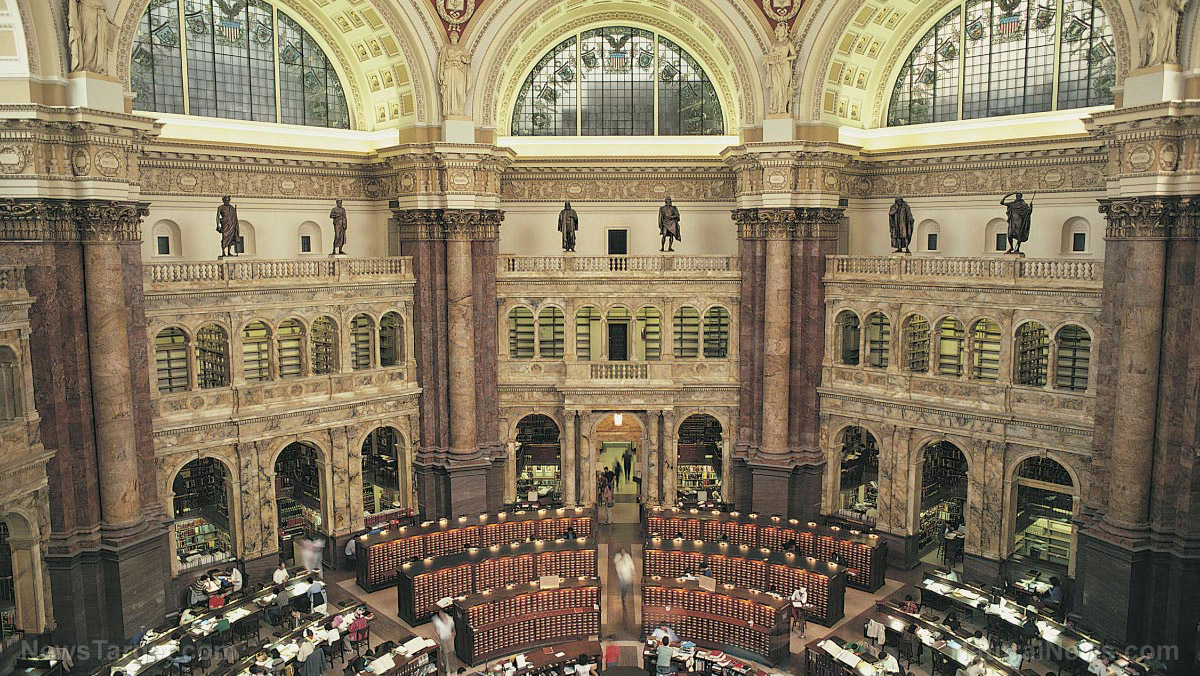

- The Library of Congress faced two major fires in its history: In 1814, British troops burned the Capitol and destroyed the library, and in 1851, a chimney fire destroyed two-thirds of its collection.

- After the 1814 fire, Thomas Jefferson sold his personal library of 6,487 books to Congress, transforming the library into a national repository of diverse knowledge despite political controversy.

- The 1851 fire prompted Congress to commission a fireproof cast-iron library room, marking a significant step in fireproofing and preservation efforts.

- These fires not only caused irreplaceable losses of historical texts but also reshaped the library’s mission, leading to innovations and its eventual expansion into a standalone building in 1897.

- Today, the Library of Congress houses over 170 million items, symbolizing resilience, but the fires remain a stark reminder of the fragility of knowledge and the importance of preservation.

The Burning of Washington turned a fledgling nation's national library to ash

The Library of Congress was born in 1800 as a modest collection of mostly legal texts housed in the Capitol. By 1814, it held about 3,000 volumes, a small but significant repository of knowledge. In August of that year, during the War of 1812, soldiers of the British Empire marched into Washington, D.C. and set fire to government buildings, including the Capitol and the library housed within it. The destruction was swift and total – or so it seemed. Conflicting accounts from the time suggest that some of the library’s contents may have been saved. Two clerks, S. Burch and J.T. Frost, claimed they had evacuated “the most valuable books and papers” before the fire, hiding them in a safe location. In a letter to the Librarian of Congress, they wrote, “A number of the printed books were consumed, but they were all duplicates of those which have been preserved.” Yet, official reports from Congress declared the entire collection lost. If any books were saved, their fate remains a mystery, leaving historians to wonder if fragments of the original library still exist, hidden or forgotten. The loss of the library struck a chord with Thomas Jefferson, who offered his personal collection of 6,487 books to Congress as a replacement. Jefferson’s library, one of the largest private collections in the nation, was a treasure trove of philosophy, science and literature. In a letter to Samuel H. Smith, Jefferson wrote, “I have been 50 years making it, and have spared no pains, opportunity or expense to make it what it is.” Congress purchased Jefferson’s library for $23,950 in 1815 – nearly $500,000 today – though not without controversy. Members of the opposition Federalist Party objected to the inclusion of “philosophical” and foreign-language works, but the acquisition laid the foundation for the modern Library of Congress. Tragically, much of Jefferson’s collection would later be lost in the 1851 fire, a cruel twist of fate that underscored the library’s vulnerability.The Second Fire: A Christmas Eve Catastrophe

By 1851, the Library of Congress had grown to encompass over 55,000 volumes. However, like the previous collection, it remained housed within the Capitol – a building prone to fire hazards. On Dec. 24 of that year, a faulty chimney sparked a blaze that ravaged the library. Firefighters, exhausted from battling another fire the night before, were slow to respond. By the time the flames were extinguished, 35,000 books — nearly two-thirds of the collection — were destroyed. The loss was staggering. Among the casualties were two-thirds of Jefferson’s donated books. The fire prompted Congress to take action, commissioning architect Thomas U. Walter to design a fireproof cast-iron library room within the Capitol. Completed in 1853, the ironclad structure was a marvel of its time, though it was eventually dismantled in 1901 as the library outgrew its confines. The fires of 1814 and 1851 were more than just physical disasters; they were cultural catastrophes. Each blaze erased unique texts and artifacts, fragments of history that can never be fully recovered. Yet, these tragedies also spurred innovation and growth. Jefferson’s library transformed the institution into a national repository of knowledge, while the 1851 fire led to advancements in fireproofing and the eventual construction of the library’s iconic standalone building in 1897. Today, the Library of Congress houses over 170 million unique items, a testament to its resilience. But the fires serve as a reminder of the fragility of knowledge and the importance of preserving it. As historian William Dawson Johnston noted in 1905, the story of the library’s survival — and the mysteries of what was lost — bears repeating every century or so. In an age of digital archives and instant access, the lessons of these fires remain as relevant as ever: knowledge, once lost, is often gone forever. One of the major problems that come with great institutions like the Library of Congress is that, if the knowledge contained within these monuments is threatened – such as with devastating fires – it could result in the immediate loss of a great amount of knowledge. (Related: Futurist John Petersen: The future of knowledge lies in DECENTRALIZATION through AI and open-source innovation.) One of the best solutions to this problem is the decentralization of knowledge. Brighteon.ai by Mike Adams, the Health Ranger, constitutes one of these decentralized archives of human knowledge. It is free and uses open-source content on the internet to benefit all of humanity. Watch this episode of the "Health Ranger Report" as Mike Adams, the Health Ranger, discusses the necessity of decentralizing knowledge sources. This video is from the Health Ranger Report channel on Brighteon.com.More related stories:

Per Mike Adams, bring back MISSING INFORMATION that is the real source of MISINFORMATION, and heal millions of sick people almost instantly. World governments seizing domain names of Z-Library to exterminate human knowledge, force everyone into controlled Big Tech info-prisons. Human knowledge is under attack by Big Tech and Big Government – here's what we are doing to preserve and share the lifesaving knowledge that has been targeted for extermination. Health Ranger to launch AI open-source health and nutrition knowledge repository that's free for everyone. The real purpose of Wikipedia is to SUPPRESS human knowledge, not document it. Sources include: Grunge.com Blogs.LOC.gov DCist.com Brighteon.ai Brighteon.comBy News Editors // Share

By Lance D Johnson // Share

Trump revives push for NUCLEAR ARMS REDUCTION talks with Russia and China

By Kevin Hughes // Share

The big freeze at HHS, CDC, and NIH

By Finn Heartley // Share

CBP One app shutdown as mass deportations of illegal aliens begins

By News Editors // Share

Governments continue to obscure COVID-19 vaccine data amid rising concerns over excess deaths

By patricklewis // Share

Tech giant Microsoft backs EXTINCTION with its support of carbon capture programs

By ramontomeydw // Share

Germany to resume arms exports to Israel despite repeated ceasefire violations

By isabelle // Share